The economic, political and demographic policy of the new regime was summarized by the slogan "To govern is to populate", which was formulated by the politician who had inspired the Constitution, Juan Bautista Alberdi. The objective of this policy was to fertilize the vast lands of the Pampas in order to permit agriculture and the exportation of produce.

Justified by a powerful ideology that opposed "civilization and barbarity", this policy consisted on the one hand in waging a domestic war against the Amerindian populations, driving them off their land, and against the gaucho nomads, who were essentially cattle breeders. On the other hand the government planned the massive importation of European labour which it invested with the dual mission of civilization and production. The Constitution proclaimed that the country intended to "ensure the benefits of liberty to ourselves, to our descendants and to all men in the world desiring to live on Argentinian soil". According to its logic, the emigrants should have come from the north of Europe, whose inhabitants were considered to be closer to the ideal of civilization. However, this is not what happened, for the majority of the newcomers originated from Italy, Spain, Eastern Europe and other European countries. According to the Argentinian authorities themselves, the policy of intensive population of rural regions proved to be a failure in the following decades. While some European emigrants managed to build farms and prosper, the greater number ended up establishing itself in the urban areas of Argentina or neighbouring countries.

It was in Argentina that most of the emigrants from the Valais settled starting in 1855 and until the beginning of the 20th century. One can observe a distribution among the various colonies according to the home linguistic region, with the French-speaking Valaisans going to the colonies of Esperanza and San José, while those from the Upper Valais went to the colony of San Jeronimo Norte. The latter was one of the rare colonies that did not organize punitive expeditions or conduct exterminations of the native populations.

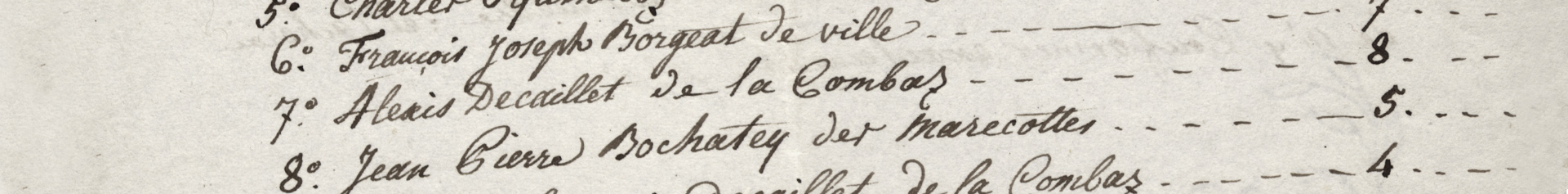

The organization of the emigration was made to a large degree by the general agency Beck & Herzog in Basel, which regularly published advertisements in the Valais papers and recruited in the canton through the intermediary of local agents: the notaries Eleuthère Besse in Sion and Martin Pache in Martigny. The large number of departures for Argentina motivated the government of the Valais to decree in December 1856 the first cantonal regulation on emigration, obliging agencies to apply for an official permission in order to practice.

The foundation of San Jeronimo Norte

In 1857, a group of emigrants from the Upper Valais left Sion for Argentina by way of Antwerp. The emigrants, who were led by the Lorenz brothers and Johannes Bodenmann from the village of Grengiols, came mostly from the Conches Valley and the districts of Rarogne and Loèche. The group separated after arriving in Buenos Aires, with most of the Valaisans heading for Entre Rios, while the rest went in the direction of the province of Santa Fe.

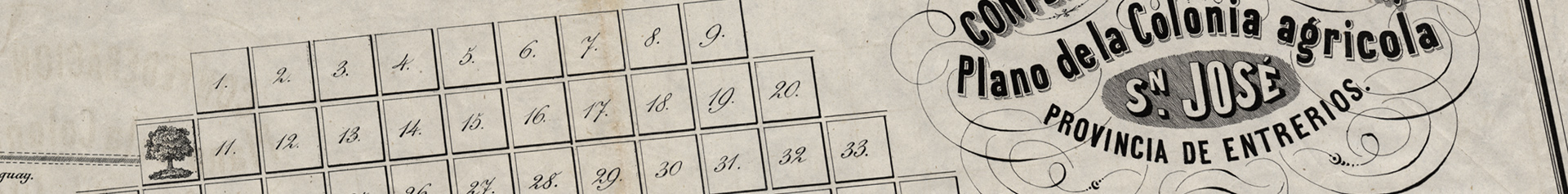

The province of Santa Fe played a pioneer role in the Argentinian immigration: the government of the province implemented the policies and sought to recruit colonists in Europe. Each family was offered some 33 hectares of land at very favourable conditions. The Valaisans took the recruitment of their compatriots in hand themselves: once the immigrants from the Upper Valais had settled in the province of Santa Fe, Lorenz Bodenmann returned to the Valais to accompany another contingent of settlers to South America.

The Bodenmann convoy left the Valais in April 1857 and settled in the province of Santa Fe in August 1857, near the native reservation of San Jeronimo del Sauce, 40 kilometres west of the provincial capital. Through the intermediary of a member of the immigration commission, the settlers were given their land on the condition of working on it for at least four years. Five years after the beginning of the colonization, there were 107 settlers occupying 115 concessions. In 1870, 236 families (1,120 persons in all) lived in San Jeronimo, with more than 180 of these families originating from the Upper Valais. The colonists worked without benefiting from any advances from the colonization firms; few colonists suffered as much from deprivation as the Valaisans. The latter demonstrated a particularly strong sense of identity and unity. They adapted to the new agricultural methods, but on the cultural level they were firmly attached to their homeland in the Valais. The Valaisan colonists were satisfied with the relationships inside the colony and saw no need to learn a foreign language. They took their distances from other colonies, not only culturally but also in terms of religious faith, for many of the colonies in the regions were Protestant. In 1872, the Valaisans of San Jeronimo founded their own shooting club; on 1st August 1891, the 600th anniversary of the Confederation was solemnly celebrated by the Swiss at home, but with great pomp in the Swiss colonies in Argentina.

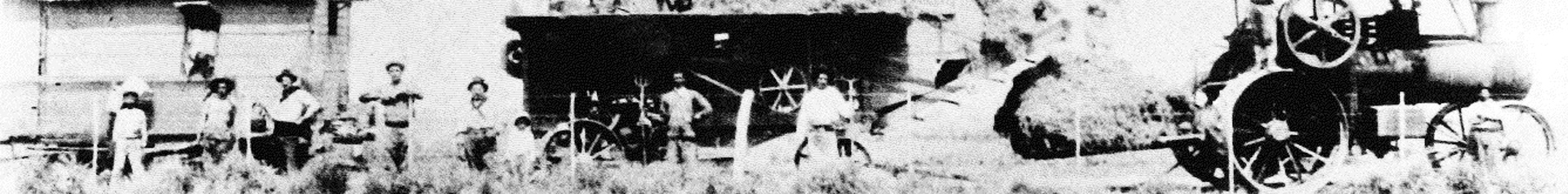

The colonists were given their land for free, which is why they did not immediately feel the pressure of the market economy. Moreover, the Valaisans preferred to breed cattle and did not have an easy time familiarizing themselves with agriculture. Their self-sufficiency was guaranteed from the start, and this slowed down their integration into the Argentinian market. The large Valaisan families—ten to twelve children per family was not unusual—was better suited to breeding cattle than farming. The development of new agricultural techniques gradually facilitated the assimilation of the Valaisan colonists into the Argentinian market. At the turn of the century, the agriculture at San Jeronimo reached a technical level that would have been difficult to imagine in the Valais. It was at this time that the dairy economy truly got underway in the Upper Valais colony. After the devastating grasshopper plagues, it seemed that livestock was less vulnerable to crises than farming. San Jeronimo is still a major centre for the dairy industry today.

At the beginning of the colonization, the immigrants from the Valais were more preoccupied by material than by political problems. The colony was an economic success and the settlers wanted to protect the achievements and merits of their labour. Self-determination on the municipal level and the appointment of judges was already a consideration at the beginning of the phase of colonization. During the 1890s, several politically motivated societies were created. There were even revolutionary uprisings, especially because of the tax on grain. This tax was all the more a bone of contention as it was levied to fill the empty treasury of the government of the province of Santa Fe. The colonists took up arms and the settlements—San Jeronimo in particular—became centres of opposition to the provincial government. Even if the situation calmed down in 1898, it justified the colonies in keeping a deliberate distance from Argentinian culture. The colonists liked to point out how much more stable the Swiss political system was than the Argentinian. Until 1900, teaching in the parish schools of San Jeronimo was done in German and one of the most popular newspapers was the Argentinisches Volksblatt, which was printed entirely in German. Hispanization was imposed in the 20th century nevertheless, but did not progress at the same rate everywhere: this process went faster in the cities than on the isolated farms that had little contact with the outer world.

In the 1980s, 95% of the 5,000 inhabitants of San Jeronimo came from the Upper Valais; a good half of them still spoke the dialect of the Upper Valais. The 1st of August is still celebrated in the colony today.

Bibliography

Alexandre CARRON & Christophe CARRON, Nos cousins d’Amérique. Histoire de l’émigration valaisanne en Amérique du Sud au XIXe siècle (2 vols.). Sierre, 1989 and 1990.

Alexandre CARRON, "Les 125 ans des colonies Esperanza, San José et San Jeronimo en Argentine: un aspect de l’émigration valaisanne outre-mer au XIXe siècle", in Annales valaisannes, 58/2 (1983), pp. 113-136.

Klaus ANDEREGG, "Die Kolonie San Jéronimo Norte in der Argentinischen Pampa", in T. ANTONIETTI & M.-C. MORAND (ed.), Valais d’émigration / Auswanderungsland Wallis, Sion, 1991, pp. 161-183.

Patrick WILLISCH, "Das Wallis in Bewegung. Ein Forschungsbericht zur Migrationsgeschichte im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert", in Blätter aus der Walliser Geschichte, 48 (2016), pp. 85-172.

Joachin MANZI, "L’accueil de l’immigrant dans l’invention de l’Argentine moderne", in V. DESHOULIÈRES & D. PERROT (ed.), Le don d'hospitalité: de l'échange à l'oblation, Presses Universitaires Blaise Pascal, 2001, pp. 113-136.